Making Crypto Multiplayer

August 14, 2023

From the earliest days of Ethereum, crypto’s power as “programmable money” gave rise to narratives around exciting new forms of group coordination on the internet. But despite almost a decade of consistent development and innovation in the Ethereum ecosystem, this potential remains one of crypto’s most elusive promises. Crypto is now approaching a pivotal moment, where the foundations of ownership and exchange of value have reached a tipping point in terms of usability and proliferation. Though market performance may indicate otherwise, crypto is on the brink of an exciting shift, where groups of people can begin using Ethereum to coordinate in entirely new ways.Internet Money

Though we don’t commonly see it through such a lens, money is ultimately a tool for coordination. In his book The Ascent of Money, Niall Ferguson introduces this concept in these terms:

Money is the root of most progress…The evolution of credit and debt was as important as any technological innovation in the rise of civilization, from ancient Babylon to present-day Hong Kong. Banks and the bond market provided the material basis for the splendours of the Italian Renaissance. Corporate finance was the indispensable foundation of both the Dutch and British empires, just as the triumph of the United States in the 20th century was inseparable from advances in insurance, mortgage finance and consumer credit…Behind each historical phenomenon there lies a financial secret…

Crypto has a clear place in this chronology. The internet has always connected us socially, allowing us to transfer information anywhere across the globe nearly instantly and for free. But it has never done so economically in the same kind of open, permissionless way. The story of payments on the internet is basically bank transfers, credit card processing, PayPal, and later Venmo and Cash app.

But in 2009, the Bitcoin whitepaper changed this. Bitcoin introduced the concept of a blockchain - a shared public ledger with its own native asset. It gave us “internet-native money.” In 2014, Ethereum pushed this even further, creating a blockchain paired with its own virtual machine and a Turing-complete programming language. It was this invention that turned crypto from “internet money” into “programmable money.”

This was a key unlock for the internet. What could happen if transferring value and setting up ownership arrangements had a programming framework as open and flexible as HTML and Javascript? Phrased differently: What happens if you combine 2 of humanity’s most important inventions: money and software?

The DAO

In the early days, one of the most exciting narratives around “programmable money” was that you could program rules for coordination. And just a few months after Ethereum’s mainnet launch, we got a famous early example of this. In June of 2016, a few early Ethereum developers launched their new project, simply called “The DAO.” It was the first ever instance of a concept that Vitalik Buterin had coined in the Ethereum whitepaper: “Decentralized Autonomous Organization.”

DAOs, as formulated, would allow people to program new kinds of social and economic arrangements, where rules were transparent and enforced automatically by code. “The DAO” itself offered the first real example of what this could look like.

The DAO would use Ethereum tech to let investors from around the world pool their funds, then vote on how to deploy it. It was likely the first global investment fund in human history open to anyone with a pulse. - CoinDesk

This first instance, though crude, immediately resonated. The concept was so exciting that within the span of a week, the DAO had raised over 150 million dollars, or 15% of all value on the Ethereum network.

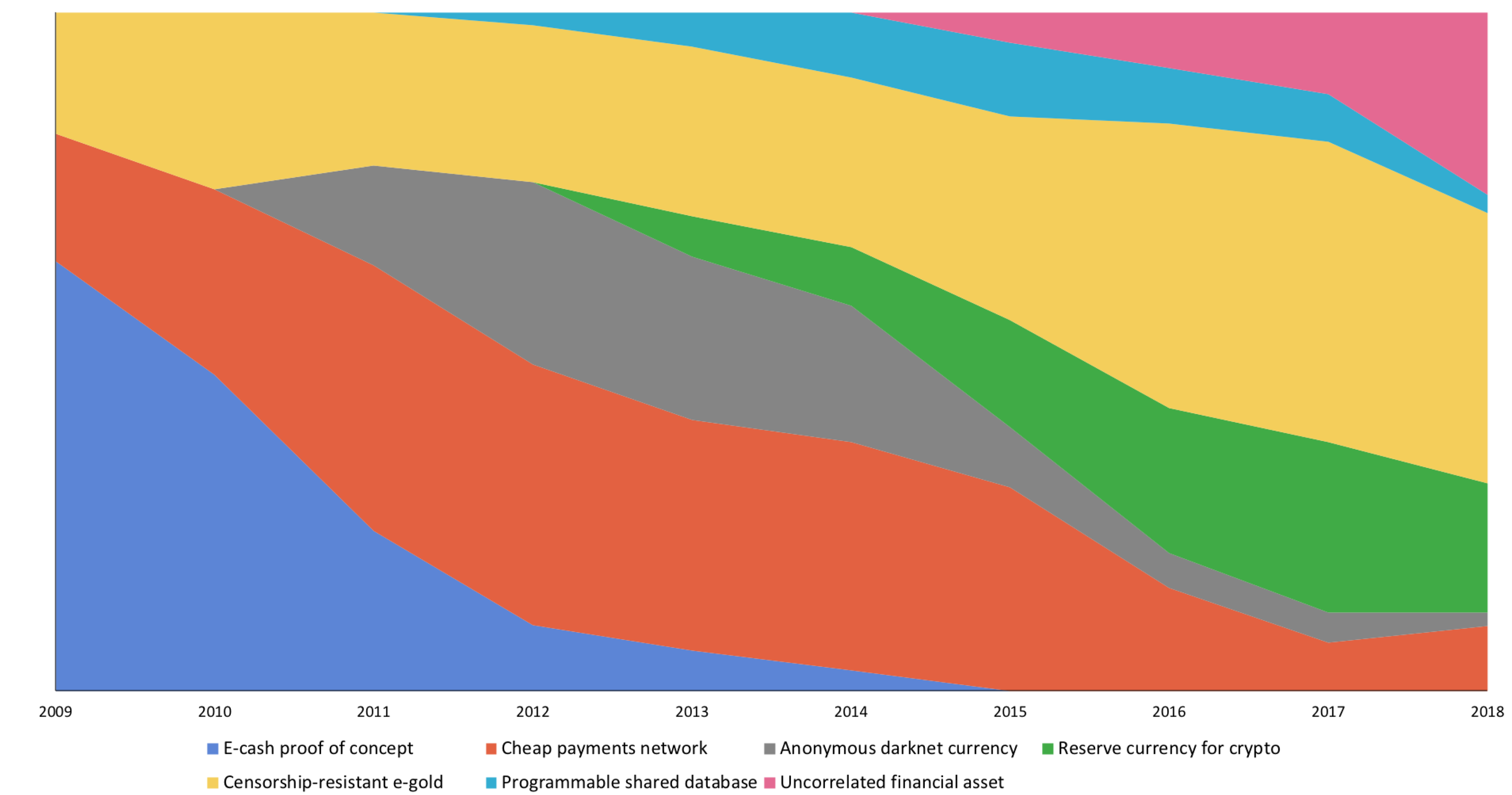

This moment felt like a turning point. Crypto thus far had been perceived largely as a technology for the so called “Sovereign Individual,” largely playing off narratives such as censorship-resistant digital gold, anonymous darknet currency, or simply a cheap P2P payments network.

The DAO was different. It showed a glimpse at a future where groups of people could use this technology to coordinate not just socially, but economically, on the internet. This sounds simple, but given that the internet had totally refactored how we organize socially, it now seemed hard to imagine what could happen if people could program new kinds of economic structures as well.

In this chart from Visions of Bitcoin by Nic Carter and Hasufly, we see some of the competing narratives in the Bitcoin ecosystem up to 2018.

But just as quickly as The DAO began, it came to an abrupt ending. A week after launching, The DAO was exploited, with a third of its funds being drained by a hacker through a now-famous vulnerability in its code. There was a long ensuing debate regarding how to respond, but it ultimately ended in a controversial hard fork – the most abrupt break in consensus that can happen to a blockchain.

The DAO is a story of missed potential. It pointed towards a future where groups of people on the internet would gain totally new abilities. But despite lots of development since then, this potential has yet to be fully realized. To me, this is crypto’s biggest unfulfilled promise. So almost a decade into Ethereum’s existence, why hasn’t this happened yet?

Markets and Bubbles

To really understand the answer, I think it’s important to cut through the predominant narrative and understand what makes crypto, and its progression, so unique. More so than any other tech platform shift, crypto is intrinsically linked to markets.

Being “internet money,” the first thing crypto did was create always-on markets running at internet speed. Blockchains themselves, and many of the projects built on top of them, have tradable tokens or instruments from day one. This is notably different from other industries or tech verticals where assets only hit public markets once stable, public businesses have formed.

These markets, combined with an exciting new technology, have given crypto a proclivity towards bubbles. This isn’t an exact science, but the mechanics of a bubble go something like this.

- A bubble starts with an Innovation or Opportunity. People see a technology that shows a lot of promise and they want to get in early.

- The prospect of quick returns attracts a rush of Speculative Investments, which leads to an increase in asset prices, reinforcing the initial optimism.

- Investors continue to buy assets at inflated prices out of Irrational Exuberance, believing they can sell them at an even higher price. Asset prices diverge from their intrinsic value, creating a speculative bubble.

- Eventually, a tipping point is reached when investors realize that asset prices are unjustifiably high compared to their intrinsic value, leading to a Bursting of the Bubble.

Bubbles are a part of all markets. They reflect human emotions. And bubbles are not all bad. Though they often leave financial devastation in their wake, bubbles can also serve to accelerate the funding and development of ambitious new innovations that would not otherwise get off the ground. A historical example is the Railway Mania of the 1840s, where even though there was a great financial cost and an eventual bursting of the bubble, the net result was vast growth in the British railway system.

The difference with crypto, however, is the speed and volatility at which these market cycles take place. Crypto markets are what happen when you take the ingredients for a bubble and accelerate them to internet speed. A new technology, wrapped in digital assets that anyone can buy, with always-on markets running 24/7. The result is relatively predictable.

For most people, these market cycles tend to be the whole story. Currently sitting about a year and a half into a classic bear cycle, this is clearer than ever. People are excited when things are up, and then move on to other things, like AI, when prices are down. But these market cycles are just the most visible signal of what’s happening in crypto. And rather than being the main story, I’d argue that the speed of these cycles is just a symptom of internet-native markets moving at their own speed.

This is a new reality of the internet, and while it only affects the crypto industry today, it’s something that everyone will need to adjust to. The same way we adapted from the 24-hour news cycle to the constant stream of information on social media, people will soon adjust to this new speed of markets as well.

Crypto's Development Progress

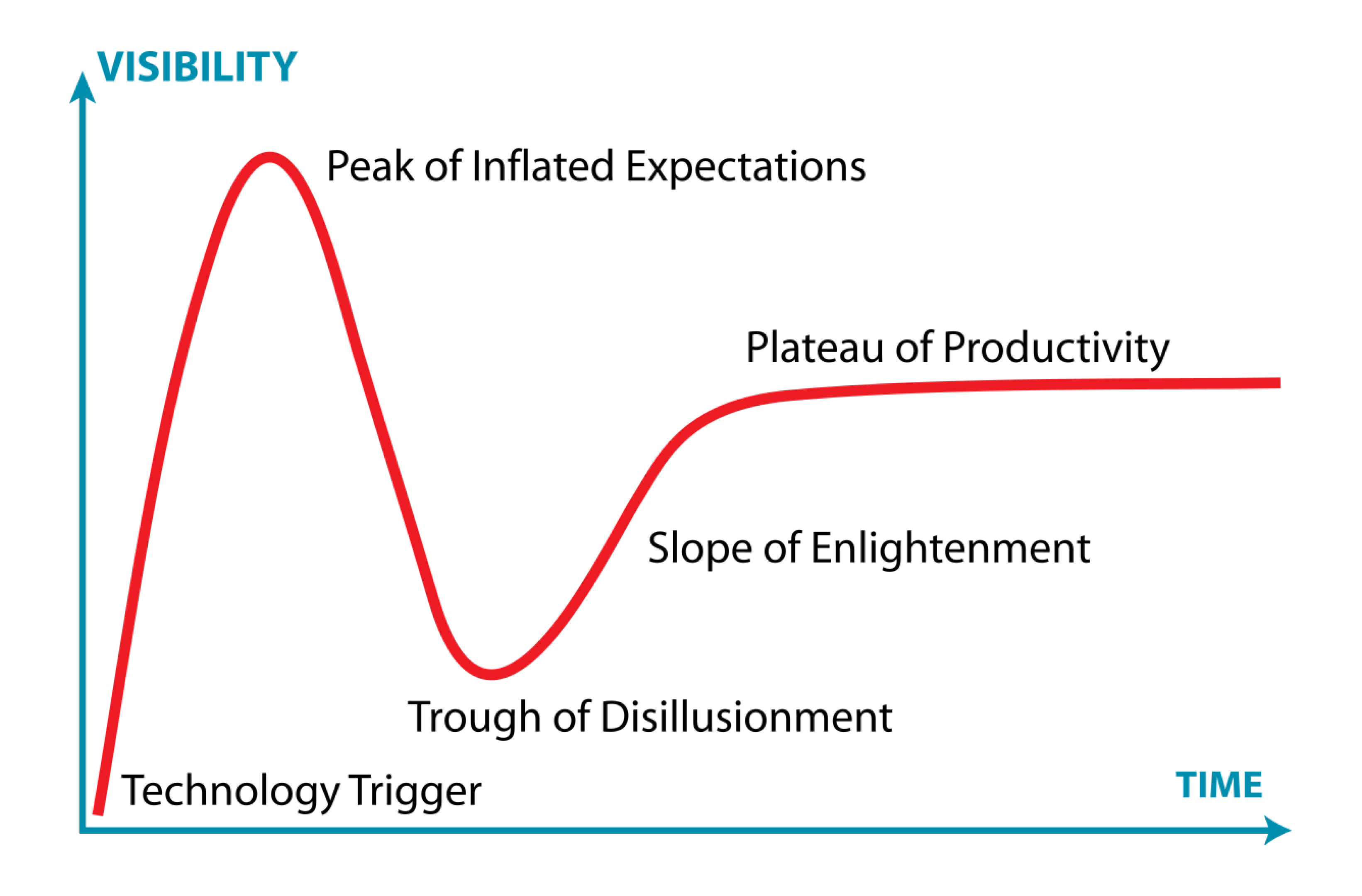

But crypto is not just a market. It’s also a technology. And while the fluctuations between bull and bear markets may be accelerated in the crypto industry, the tech adoption lifecycle is not. No matter what you do, it still takes time for new technology to get through the initial hype cycle and move on to broader adoption.

Though reductive, the Gartner hype cycle shows a generalized path that new technologies take towards maturity and adoption.

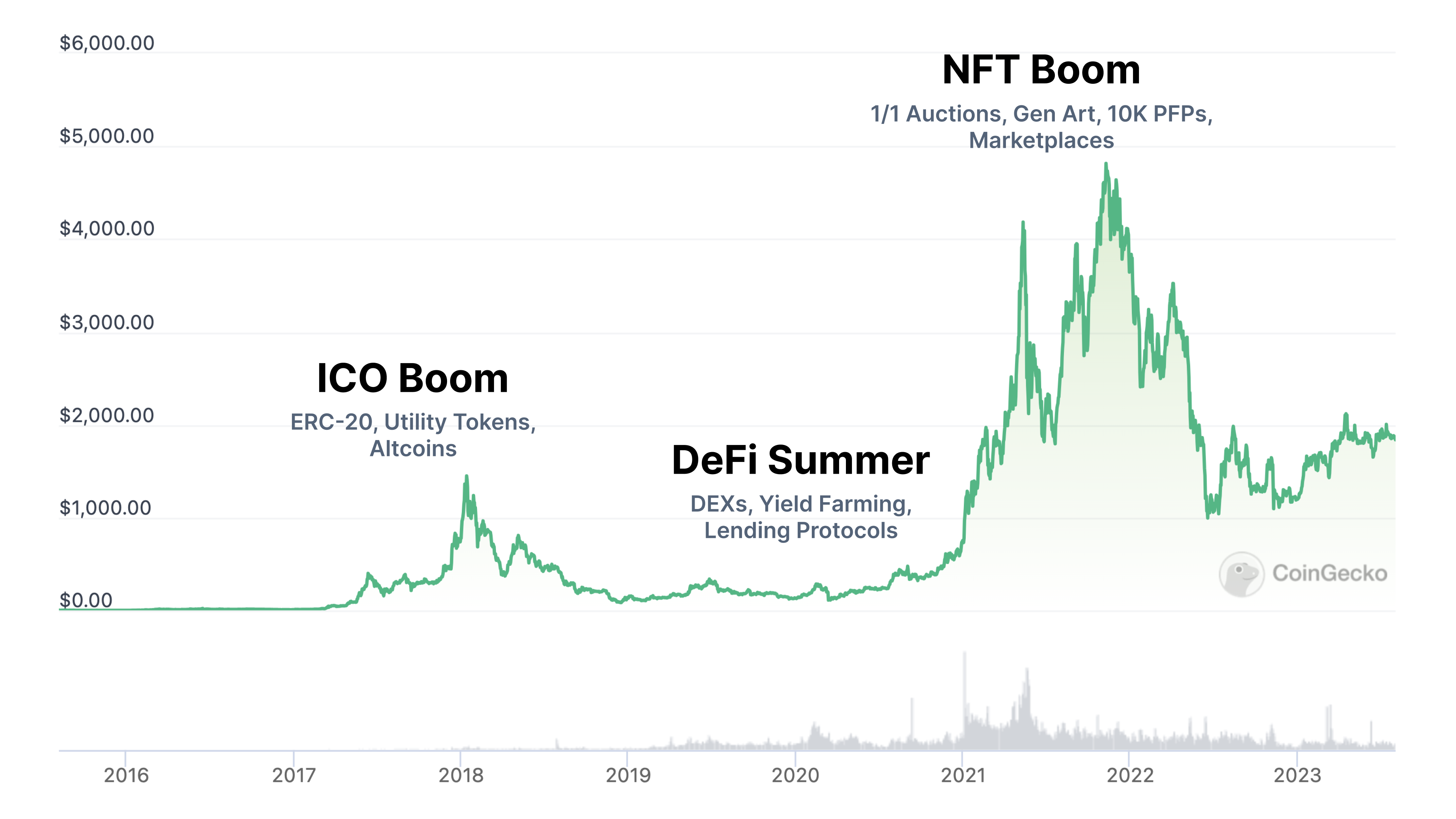

If we look at the all-time historical price chart for ETH, we can see some of the famous price run-ups and the technical innovations they aligned with. Obviously, the correlations here are not a coincidence. The biggest of these innovations were also new asset types, and their invention corresponded to a subsequent price spike.

It’s important to point out that the crashes following these price spikes did not, in fact, signal the death of the innovations that triggered them. In fact, through the lens of tech adoption cycles, these things tend to reach their plateau of productivity by the time the next wave rolls around.

For example, the 2017 ICO bubble was in large part driven by ERC-20 tokens launched on Ethereum. This eventually led to a crash, as most tokens from that era were worthless vaporware, but the core primitive of ERC-20 tokens ended up being the backbone for many of the DeFi protocols developed just a few years later.

It may look chaotic from the outside, but zooming out, it’s clear that though price spikes may correspond with new innovations, price crashes do not reset development progress. In fact, it could be said that crypto is leveraging markets to its own advantage, speedrunning market cycles to fund and accelerate its own development.

Through these separate waves, crypto has progressively built out the primitives of an internet-native value layer, with each wave laddering up a bit in terms of abstraction and complexity. From digital money and stocks, to decentralized finance, to digital objects, to NFT marketplaces, the primitives developed thus far have laid the groundwork for ownership, exchange of value, and composability. And for the small early adopter pockets of the internet, these primitives have already started organizing the way people behave.

I would posit that crypto’s development thus far is not much different than any other platform shift. It’s just exaggerated by its coupling to markets.

Making Crypto Multiplayer

If crypto thus far has been setting the foundation for ownership on the internet, then what’s coming next? This question is why I think it’s helpful to frame crypto itself as money plus software. Through this lens, it’s clear that while on-chain ownership may be the new technology, on-chain coordination is the new behavior.

Money, markets, finance — all of these are tools for coordination. But while crypto has arguably succeeded at this in the economic sense, what it’s missed out on is what happens when you inject social trust and alignment into these dynamics.

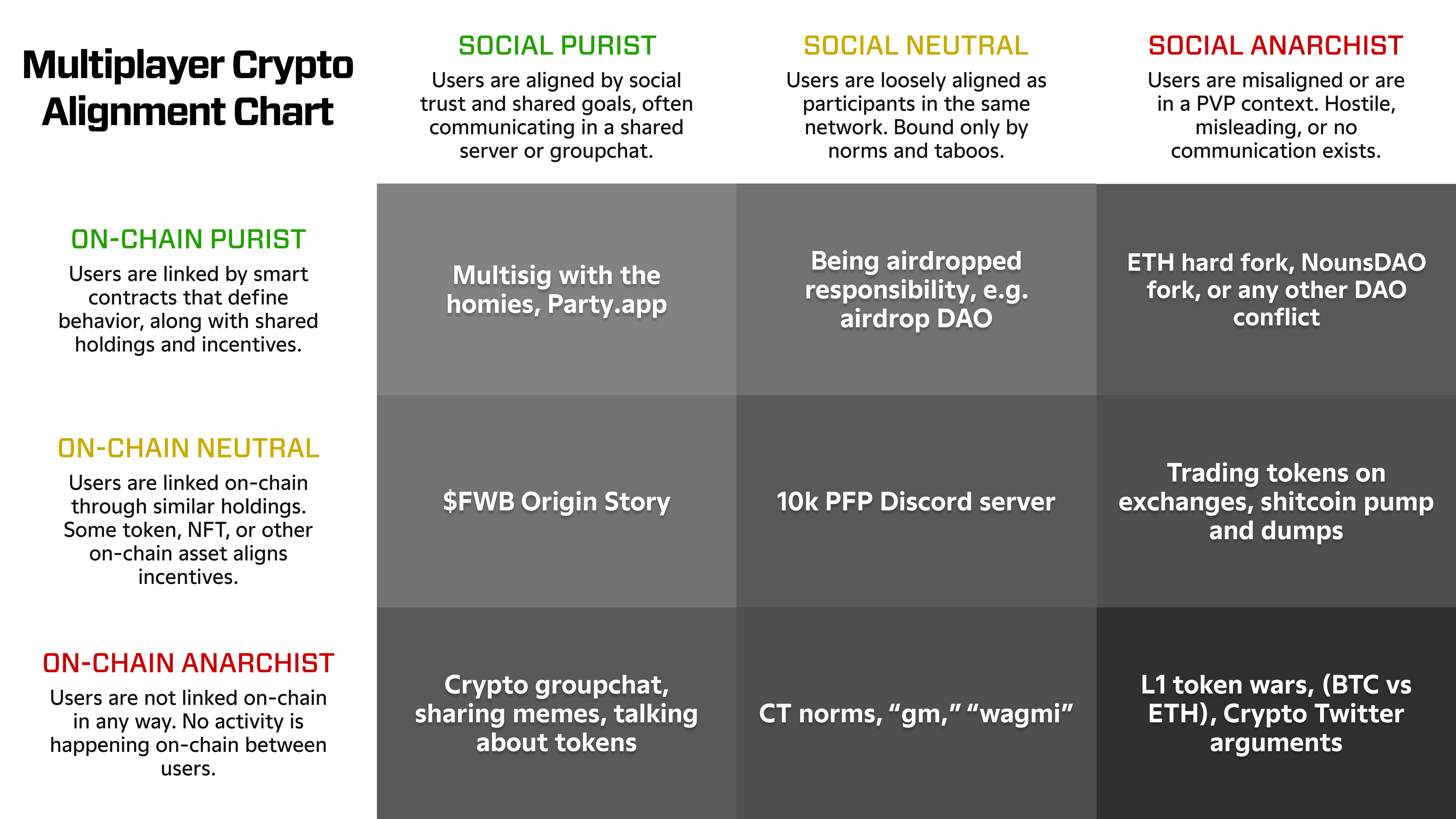

In our work at PartyDAO, we build tools for exactly this, which we refer to as “making crypto multiplayer.” This phrasing is more charismatic than precise, so to understand this better, I think it’s helpful to map out the crypto landscape along two axes: the social and the economic. Below, this is illustrated by the Multiplayer Crypto Alignment Chart.

While all of crypto may be thought of as "multiplayer" to some degree, the top-left regions above capture more tightly coordinated group action.

Looking at this chart, if you were to map out crypto’s progression over time, I think it’s clear that we’ve been moving up and to the left. While behaviors in the bottom row and right column have been around for a long time and at scale within crypto, behavior towards the top-left is not only newer but has seen less adoption and scale.

This top-left territory not only has untapped potential, but is also the area where crypto could most improve the ways we organize and interact online. So why hasn’t this type of behavior had its own wave of adoption yet, despite The DAO being one of the first mainstream headlines of Ethereum?

This work, framed here as building out Ethereum’s “single player” ecosystem, is what’s taken the past decade to accomplish. But from this perspective, I believe the crypto industry is nearing a critical moment. Despite the market narrative, we’re approaching the point where this ecosystem is turning a corner. There is now a strong base of ownership and exchange primitives around which groups can gather, and for the first time, it’s becoming reasonable for groups to interact with these tools at scale.

But this directs our attention to another challenge that remains unsolved: complexity. Unlike the more pure mechanics of markets and finance, group dynamics can be messy, and they get exponentially more complex as groups scale. Before crypto can achieve its potential as a tool for group coordination, new solutions are required that address a combination of social and economic challenges.

People + Rules + Inventory

So, how do we solve for this complexity? Though the idea of on-chain groups has been around since the early days of The DAO, and notable evolutions like MolochDAOs and GovernorBravo have been invented along the way, many challenges remain unsolved. To understand better, we can learn from common ways that group coordination has broken down in different crypto projects thus far.

People

Let’s start by looking at the most essential part of any group: People. Looking to on-chain groups today, a common mistake is failing to design a thoughtful process for who can join and how, based on the group’s core objective. This is most obviously demonstrated in many legacy protocol DAOs, which were initialized via a token airdrop to all the users of the same product or protocol.

The thought process here is that users will care about the future direction of the product they use, but in practice, many users view airdrops as free money, and instantly sell their tokens on exchanges. These DAOs receive criticism for being rigid or immobile, but at this stage, this isn’t necessarily a technical problem. Rather, it’s an ownership problem that begins with group formation.

What we need moving forward are more sophisticated solutions for group formation that allow for nuance in how groups get created. An example here is the Party Protocol, which provides a range of flexible methods for starting a group, ranging from manual invites to crowdfunding methods to more nuanced rules for who can join. This means that any new group can choose the formation method that reflects its main priorities.

Rules

The next part of any on-chain group is its Rules: how the group interacts and makes decisions. A prevalent difficulty here occurs when a group has on-chain governance logic that’s not well-suited to its purpose.

One example today is the limitations of standard tools like GovernorBravo when applied in the wrong setting. This DAO governance protocol encodes a fixed-length voting period, which all decisions must go through before a decision is reached. This variable is a great safety feature, but in practice it can also be a bottleneck. It’s common for different decisions to have different levels of urgency, but all must wait through the same voting period.

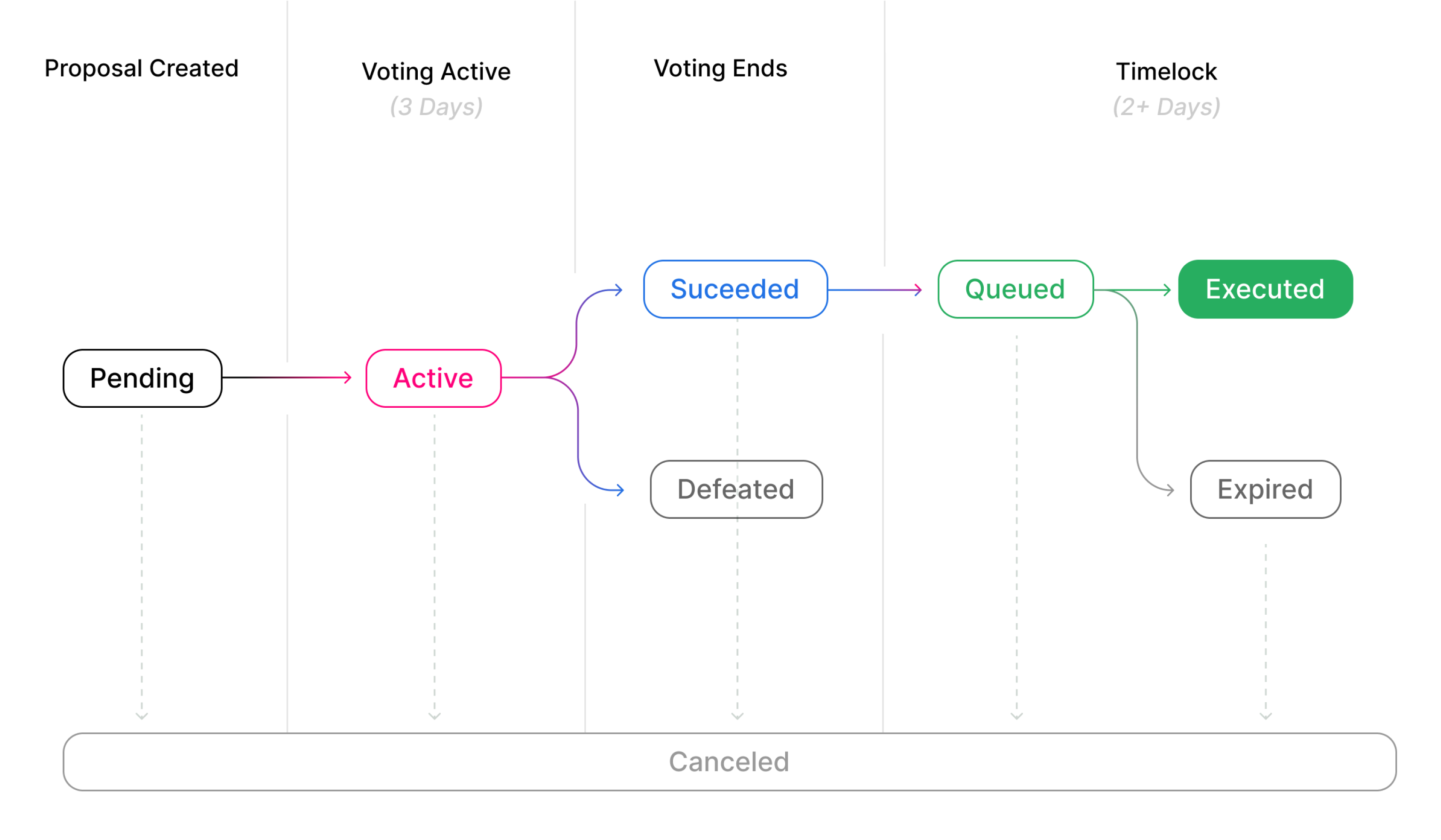

The GovernorBravo proposal lifecycle, as shown in Uniswap's governance documentation.

Some solutions in the market today get around this with “yes only” voting, like the M of N signature schema in multisig wallets or the acceptance threshold in Party governance. But the options in the market remain slim. Looking ahead, additional consensus frameworks will need to be built around the needs of various types of groups and organizations.

Inventory

A final area to investigate that’s specific to any on-chain group is its Inventory: how does the group own, earn, and make use of its assets?

Regardless of governance framework, one challenge that all on-chain groups face is the inherent tradeoff between consensus-building and speed. It takes time for a group to make decision, but this often renders the group’s inventory difficult to use.

This issue is most obviously illustrated by the common frustration of trying to perform a token swap or an NFT purchase from a multisig wallet or DAO. The group may pass a proposal to perform the action, but in the time it took to reach this decision, the market moved, rendering the transaction invalid.

However, new mechanisms can be created that allow groups of people to get around these kinds of limitations. One new solution here is a concept called “operators” in the Party Protocol. These special proposals let a group decouple decision-making from execution. For example, a Party can vote to swap some of its ETH for another token within a specific price range, but leave the execution of that trade up to a specific individual in the group to complete at a later time. This maintains group consensus around how inventory is used without holding a group back from moving at the speed of the market.

Moving Forward

If there’s one thing we know about groups on the internet, it’s that they can be very different. The internet has given us a wide range of new social structures, from message boards to subreddits to Discord servers, all the way down to the basic group chat. When we add crypto into the mix, we have a basic ontology for what defines an on-chain group. People, Rules, and Inventory.

For an on-chain group to be successful, all three of these elements must be designed around the group’s specific needs. What we need moving forward are tools and protocols that offer the nuance and customization required for groups to set themselves up for success, the way that the web’s social tools do today.

Examples and Future Potential

Given crypto’s unique technical strengths when it comes to coordination and contracts, I think it’s nearly impossible to overestimate the potential impact of solving these problems. When something becomes it internet-native, it doesn’t just get faster and easier – it invents entirely new behaviors.

A historical example like the shift from mail to email demonstrates this concept well, and we can already start to see this playing out with other tools in crypto. Tokens, which could be considered digital stocks, are not just used as stocks in companies but as tradable ownership over anything. Creation of a token is one click of a button, and a market for trading is right there too. For this reason we’ve gotten meme stocks, governance tokens, fractionalized NFTs, new financial instruments, and dynamically priced physical goods.

NFTs started with their most obvious skeuomorphic analogy, 1/1 art pieces, then quickly progressed to be generative art, 10k pfp projects, DAO memberships, on-chain objects, and digital souvenirs.

What happens when you take group coordination and make it internet-native in the same way? Though it’s still very early, there are already some interesting new models that are starting to play out today.

On-Chain Raid Parties

One example is On-Chain Raid Parties, which exist on an immediate time horizon. This type of group raises money for a finite goal, accomplishes the goal, and splits the loot, akin to a World of Warcraft raid party.

The superpowers that crypto unlock here is speed, making short-term projects significantly easier to start, and putting them entirely on rails. The group has a finite beginning and end that can be defined in code, which reduces the requirement for trust and unlocks scale on a short time horizon.

Real world examples of this behavior from crypto over the past few years are things like the ZombiePunk PartyBid, or ConstitutionDAO, both from 2021. These examples may seem niche, but they are evidence of how powerful it is to give groups fast access to formation and distribution of economic resources. This behavior is already well established in the gaming world, and crypto has the potential to extend this behavior into all other areas of the internet.

Internet-Native Companies

The next example to point to is Internet-Native Companies, which are designed for an extended time horizon. This type of group raises funds in discrete rounds, deploying capital around a series of goals in order to accrue value. The analogy here is the joint stock company, where investors and contributors can pool risk and reward, allowing them to take on more ambitious projects.

Crypto’s big unlock here is leverage and automation: heavy operational pieces like fundraising, international payroll, and cap table management become free and automatic. These groups can have dynamically updating cap tables and fundraising strategies without the human overhead of managing them.

This has the potential to lower the activation energy and number of people required to start and operate a project that eventually becomes extremely valuable. To quote Squad Wealth from Other Internet:

Civilization advances by extending the number of important functions squads can perform without thinking.

A real world example of this would be PartyDAO’s own origin story. It started with a small kickstarter-style crowdfund to build an MVP and continued evolving into a serious software organization over time.

If the barriers to creating new companies are 100 times lower, it’s possible that moving forward, more people are starting internet-native companies than traditional startups. And given the ease of creating this kind of entity, it won’t just be VC-backed tech startups. We’ll also see things like pure cultural production groups, artist collectives, labels, and so on.

Hypercultures

The final example is a specific type of DAO that some people in crypto have started calling hypercultures, which are designed to exist on an infinite time horizon. This type of group is purpose built to enable ongoing work around a simple but shared goal, gaining massive parallelization and scale at the cost of fine-tuned top-down control. These groups tend to have some core qualities: they’re open to join, co-owned, democratically governed, incentive-aligned, always growing, and have no single point of failure.

The analogy for this type of model is Encyclopedia Brittanica vs Wikipedia. The former may have a higher percentage of experts, but it’s ultimately unable to compete with the scale and persistence of the work done by Wikipedia editors. Google almost anything in the world, and there’s a high-quality Wikipedia article at the top of your results. How could this improve if the right economic were involved?

The on-chain example of this today is NounsDAO, whose goal is simply to fund good ideas while proliferating its own brand. Moving forward though, I think the power of this model is really clear. Any effort that benefits from parallelization and scale more than tight coordination has the ability to use this model as a tool. Not only could this enable more headless brands, but also larger funds and grants programs dedicated to the world’s most important problems. Scientific research, for example, is built around the goal of independent replication, and could benefit a lot from funding and parallelization in this way.

And more...

These are just some initial examples that we’re already seeing within crypto, but they’re potentially the types of structures that lots of people will participate in in the future. And based on tech history so far, there’s probably much weirder and more interesting examples to come.

Looking Forward

This essay was originally delivered as a talk in August 2023 at FWB FEST, which is billed as an "internet exposition." But whether people want to admit it or not, the event is a crypto conference to some degree. Though it's now bringing hundreds of people to the woods in California, FWB itself started with just two things: a Discord and a token. The social and the economic. Even these simple tools, combined with some trust and alignment, gave rise to something that has expanded beyond what most people could have expected.

If crypto represents an internet-native value layer, then we’ve been selling it short. Crypto offers us not only interesting new verbs on the internet, but also new ways of organizing that could improve our lives and change the way we coordinate online. And despite a decade of development with many market cycles in between, I think we’re only at the very beginning of a critical time for this technology. To use crypto language “we’re still so early.”

Special thanks

Thank you to Steven Ebert, Jordan Montgomery, and Toby Shorin for your feedback and guidance on this piece.

Get an email when I publish a new essay